California is in the midst of a particularly volatile economic time, with a great deal of uncertainty about the future. Of course, the pandemic continues to reverberate in striking and unexpected ways. At the same time, severe international conflict is affecting energy prices and creating other urgent challenges. Amid these shifts and risks, predicting even the near term direction of the economy is a challenge. Historical patterns that typically help us understand economic trends are not a clear guide today. So what can we know now about where California’s economy is headed?

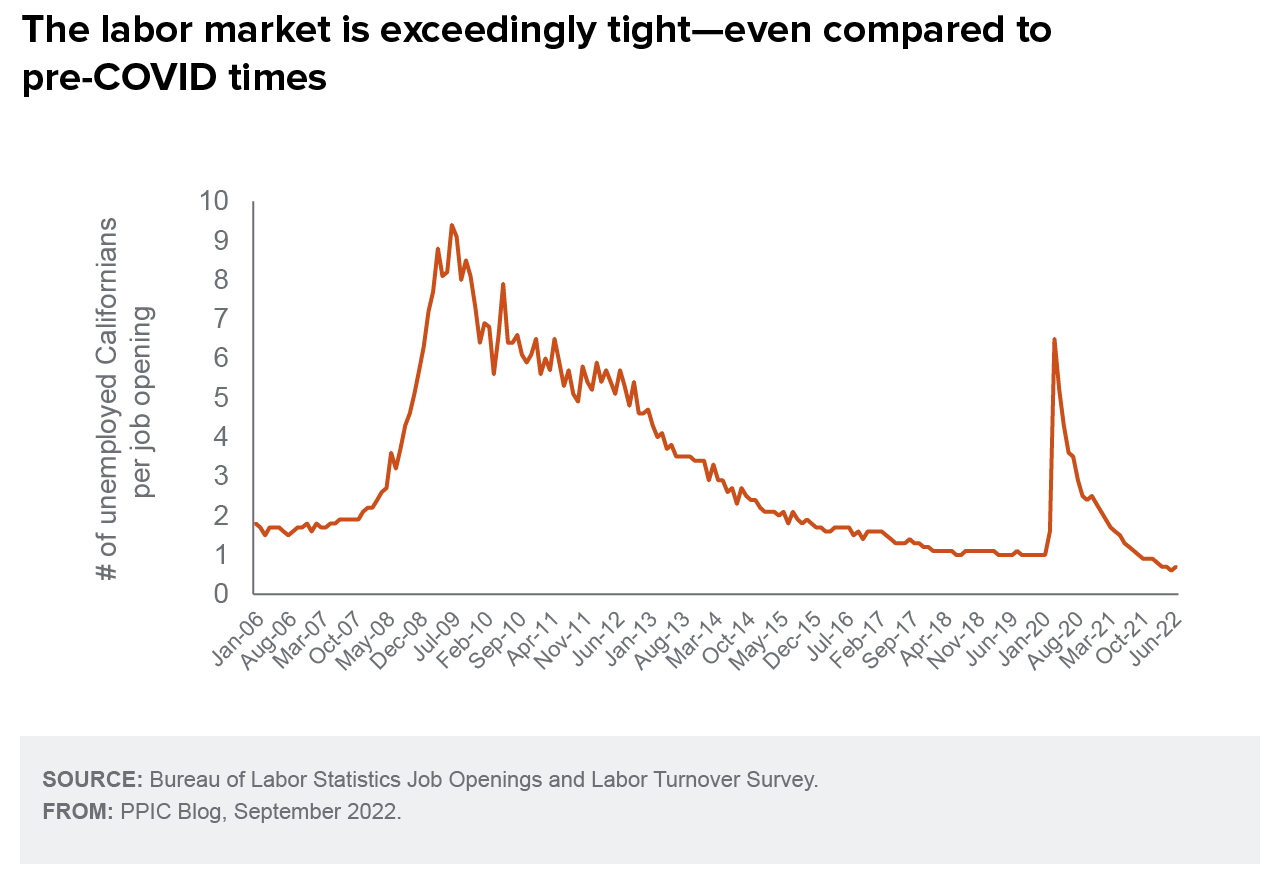

California’s recovery was swift and has even showed signs of creating equitable growth across regions and racial/ethnic groups. The unemployment rate in July (3.9%) was lower than at any point in at least the last 40 years. Key challenges today include meeting workforce needs, as employers struggle to fill job vacancies, and mitigating the substantial rise in prices over the past two years.

To understand where California’s economy is headed from here, we must examine how the fundamentals have shifted as we emerge from the worst of the pandemic—and what that means for the policy choices ahead. In my assessment, the biggest shifts have been concentrated in three main areas: where we work, live, and operate our businesses; how we work and how we want to work; and the availability of major federal investments. In each case, new realities intersect with long-standing economic challenges in California, such as the high cost of living, growing inequality, and persistent poverty.

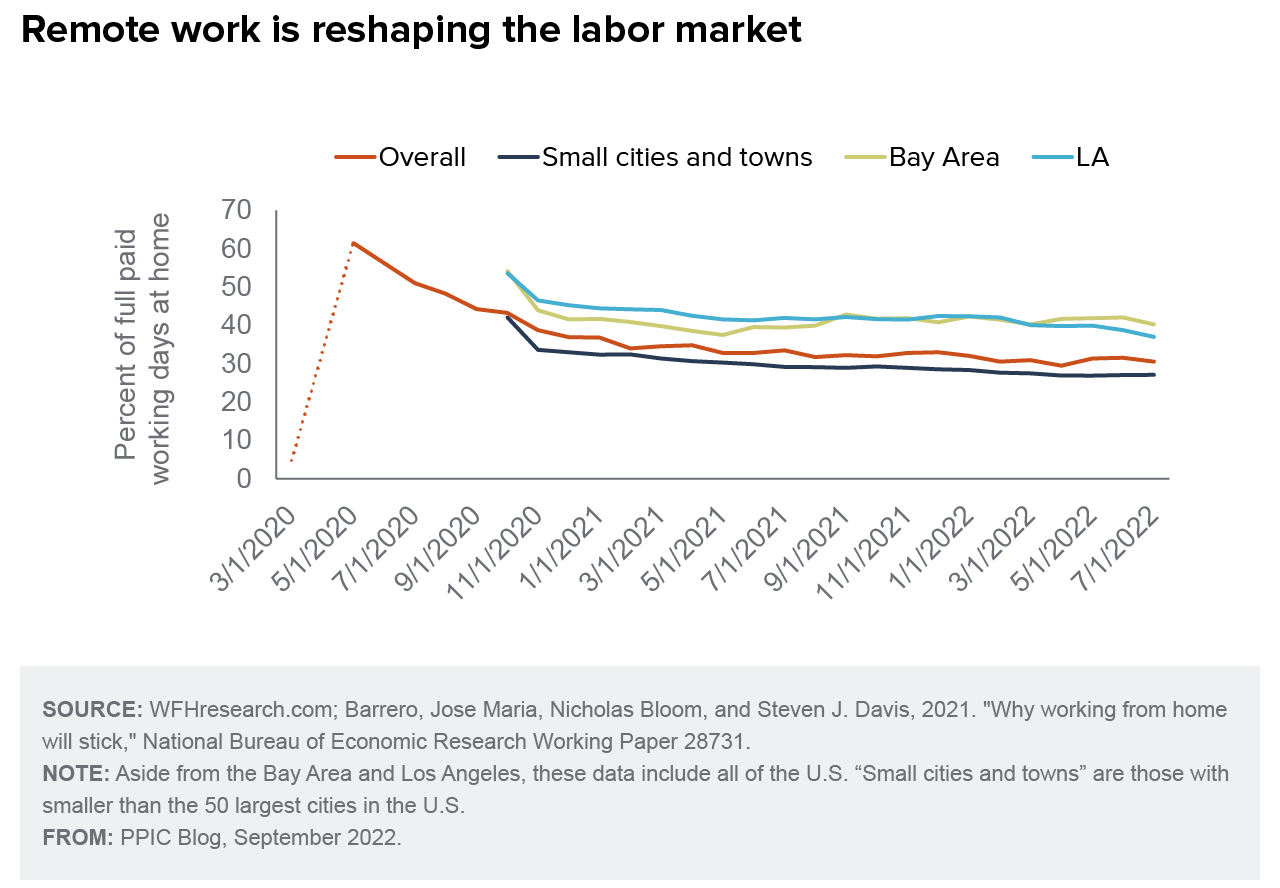

Where we work, live, and operate businesses is in the midst of seismic change. Remote and hybrid work is reshaping the home-office-business location calculus. Pre-pandemic, about 5% of working days were done at home—today, nationwide, about 30% are (that’s a little more than one day per week). In large cities and metro areas that share is even higher—37% in Los Angeles and 40% in the Bay Area (about two days per week). If the trend in remote work stabilizes around this rate—which appears to be the case in recent months—it will mark one of the biggest (and fastest) shifts in the labor market in decades.

In some sectors remote work is common, especially those that skew toward well-educated workers in higher-paying jobs and industries such as information and finance. In other mostly less well-paid sectors such as food services, transportation, and retail, it is rare. But the shift to remote work affects many sectors, and the businesses that served office workers are experiencing what now seems to be a persistent shift in demand that affects their bottom line.

California also saw shifts in where people chose to live during the pandemic, and now that remote work is settling into persistent patterns some of these shifts may become permanent. Relatedly, business locations may change as well, in response to where Californians live and work. The cost of housing and commercial real estate as well as other living expenses—all exacerbated by inflation—exerts pressure on these choices. California’s policy decisions in housing and business costs can make a meaningful difference—and even though California will remain a high-cost state due in part to its natural amenities, policy can relieve cost pressures in numerous ways.

What Californians want out of work—and what actually supports work—has crystalized in new ways. After the initial tumult of pandemic layoffs, Californians are back to work. Today, fewer residents are unemployed than before the pandemic, even with a similar share of adults in the labor force (62.4% today compared to 62.8% before the pandemic). However, a lot of shuffling is still going on, as wage growth, job openings, and quits remain higher than historical levels. Not many unemployed Californians are available to fill current job openings, stressing business’s workforce plans; long-term demographic factors like aging, slowing immigration, and increasing migration out of California are also stressors on meeting workforce needs.

Many Californians are switching jobs to take advantage of higher wages or more flexibility. However, workers tend to switch jobs within the same industry, which means that the potential benefits of higher wages and greater flexibility are limited by differences across job sectors—and therefore varies along gender, racial/ethnic, education, and income lines as well. It is critically important that job opportunity is not limited because of inequitable access to training and education. In the near term, the time it takes to seek and acquire new skills may prevent huge immediate gains for workers, but in the long term a robust, inclusive, and forward-looking approach to education and workforce preparation (or retraining) is essential for California’s—and Californians’—economic future.

One aspect of work flexibility that came into sharp relief during the pandemic is the ability to meet child and dependent care needs. Remote work offers some ability to address family care needs, but nonetheless all work requires that family care needs are being met. The state’s recent attention to developing policies to care for our youngest and oldest residents will also support a robust labor force for the future.

Federal investments have the potential to reshape the state’s future, if used effectively. Recent years have brought federal investments to states at a remarkable scale. In the worst of the pandemic, federal support to families generated a reduction in poverty and income inequality in California, while federal business relief injected billions into the state’s economy. California is still using pandemic-era federal funds to support local economic recovery and development and is preparing to deploy massive infrastructure investments and new resources to shape the climate transition. The extent to which these investments will shape the state’s economic future depends on how effectively California identifies the best uses of new funds, manages complex projects, and prepares a workforce to take on new job opportunities. This will certainly be a challenge in California, with our great diversity across regions, communities, and people. Inclusive regional approaches such as the state’s Community Economic Recovery Fund (CERF) hold promise, leveraging successful models such as Fresno Drive.

Going forward, these three major shifts are likely to change California’s economic landscape in myriad, consequential ways. Exactly how they will play out across our diverse state remains to be seen. What is clear, however, is that Californians—as workers, business owners, and policymakers—will need to adapt and work together to support a prosperous economic future for all.