Just before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, things were going very well for California’s public higher education institutions. Across all three systems, state funding levels were high and increasing, student outcomes were improving, and programs for students in need were robust. Then in March 2020, COVID-19 sent shocking changes through these educational institutions’ means and methods of operating.

Crisis hits

Almost overnight, campuses closed and students, faculty, and staff were sent home. Student and family incomes collapsed. The University of California (UC), California State University (CSU), and California Community College (CCC) systems faced a financial catastrophe similar to the Great Recession of 2008, while enduring a rampant global virus. Because of the complexity, differences in size, and unique campuses within each system, no universal solution could fix the financial and public health crisis affecting the institutions.

California’s public institutions faced potentially catastrophic financial dynamics: sharp drops in revenue from tuition, housing and dining, and auxiliary services such as parking and bookstores, as well as burgeoning costs associated with on-campus COVID-19 safety measures and with moving courses and student services online. To make matters worse, state funding also fell for fiscal year 2020–21.

Federal emergency relief was substantial and timely

The federal government was quick to pass a series of emergency relief bills—together known as the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund, $10.1 billion of which went to California. These funds were to be divided equally between student aid and defraying institutional shortfalls—originally just for the requisite move to online courses, but later expanded to cover other related costs.

Student Aid. California students received over $5 billion in emergency grant aid. The first round of funding had restrictive rules for disbursement to students. Based on campus full-time enrolled students rather than head-count totals and on the number of Pell Grant recipients (as a measure of student need), this round favored the UCs and CSUs over the CCCs. Although subsequent rounds sought to address funding inequalities, community college students got less aid per student than their university counterparts did throughout the pandemic.

Moreover, although the US Department of Education and the California public systems offered guidelines, each campus had differing challenges in getting the money to students in need. Because student information on file was based on their families’ financial situation from previous tax years, and students had moved away from campus, disbursement was a trade-off between speed and accuracy. Because the pandemic changed student and family incomes, ensuring the accuracy of disbursement was also challenging.

Especially during the first round of federal aid, the neediest students may have gone without additional aid, particularly at community colleges. Community college students often study part-time while also working, and Pell Grant uptake is low; furthermore, these students often rely on state, not federal aid, so many did not have federal aid applications on file. Those without stable home addresses and/or internet connections were most difficult to reach.

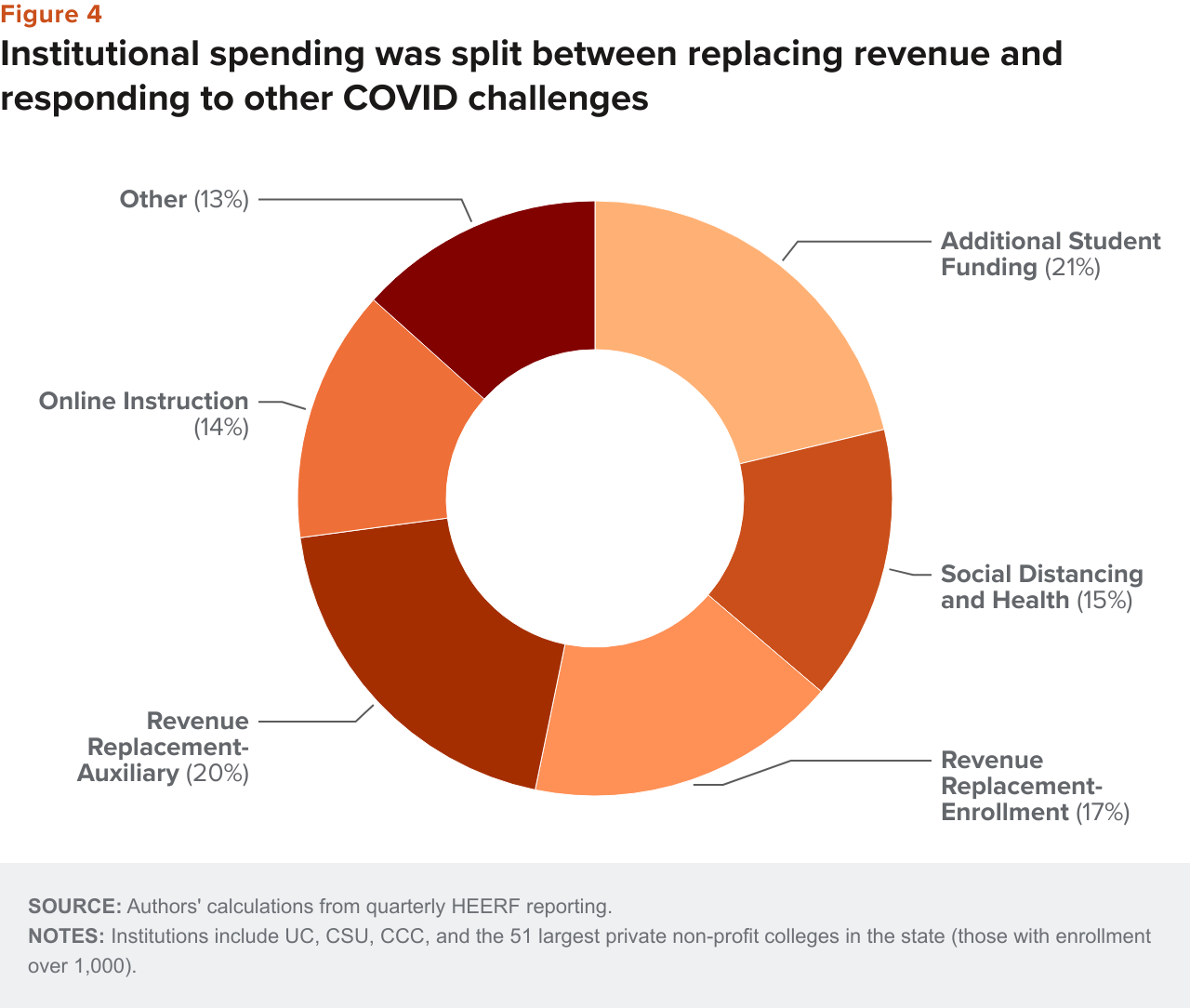

Institutional Spending. UC, CSU, and the community colleges received about $4.5 billion in institutional relief funding. In the first round, campus aid spending was limited to temporarily moving courses online, a major transition that needed to happen swiftly. During later rounds, the federal government loosened restrictions to allow aid to go to additional pandemic-related institutional expenses. Notably, most institutions used some of that funding to support students most in need beyond the student allocation portion. Although every institution has publicly posted spending information, about 13 percent of expenditures fall into an “other” category, making it challenging to understand its use.

Going forward

As of March 2022, California higher education institutions still had about a third (over $2.1 billion) of their institutional appropriations to spend. After funds are spent, evaluating allocation patterns will provide useful information on institutional finances, student retention, and student success during the pandemic. Meanwhile, the COVID-19 crisis revealed several key takeaways around preparing for similar crises and changing how learning is delivered in California:

- Emergency funding should be disbursed equitably across systems, with clear guidelines that reflect the complexity of California’s higher education landscape from the system to the campus level. Aid should go directly to campuses based on head count, not full-time equivalents or Pell Grant recipient numbers.

- To allow transparency and analysis, detailed reporting requirements should describe how “other” expenditures are categorized and suggest consistent use of all categories.

- Campuses interested in building on pandemic-motivated online education will need funding to maintain infrastructure as well as more information on how online education affects student outcomes, especially for those without reliable device and internet access.